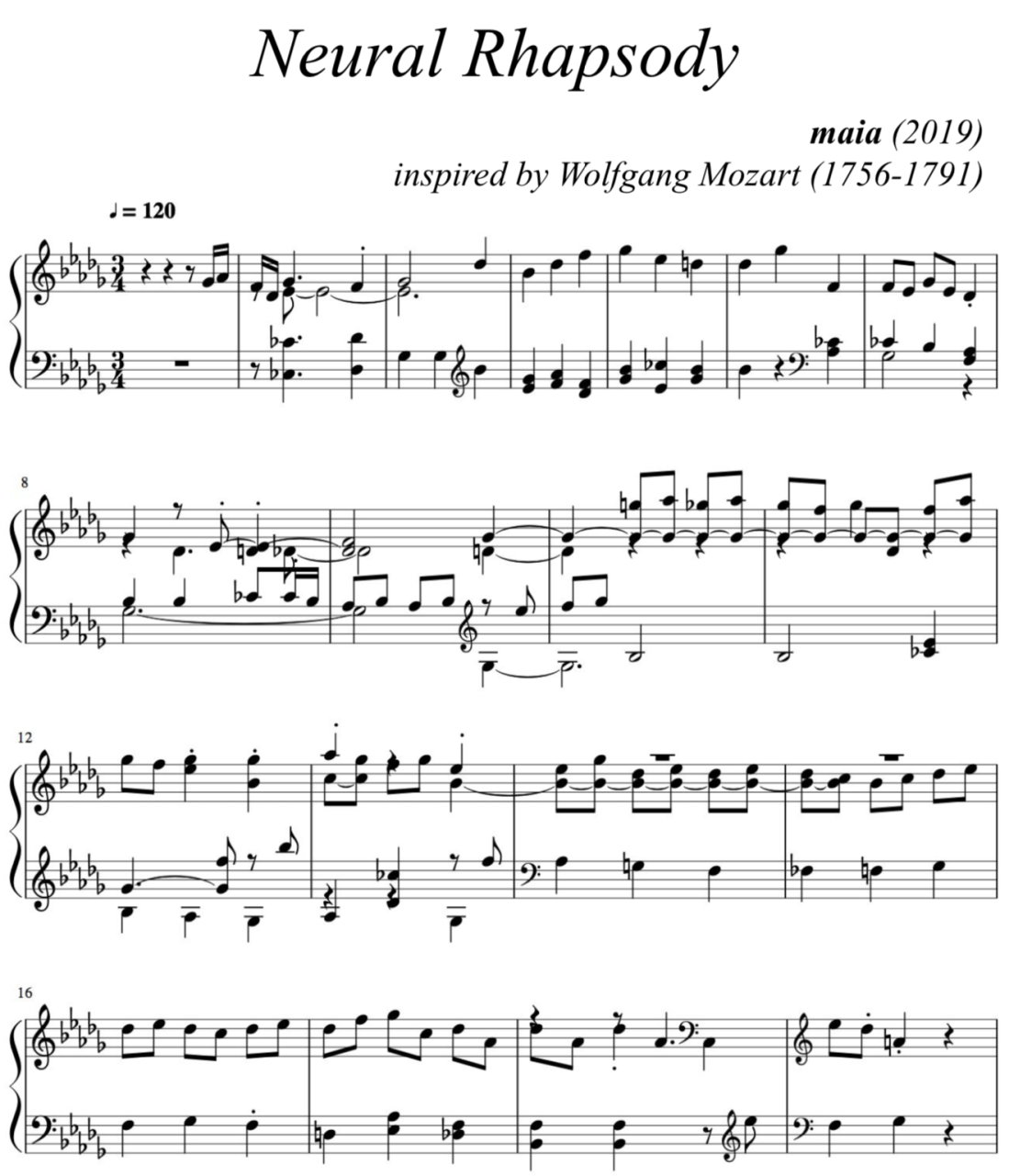

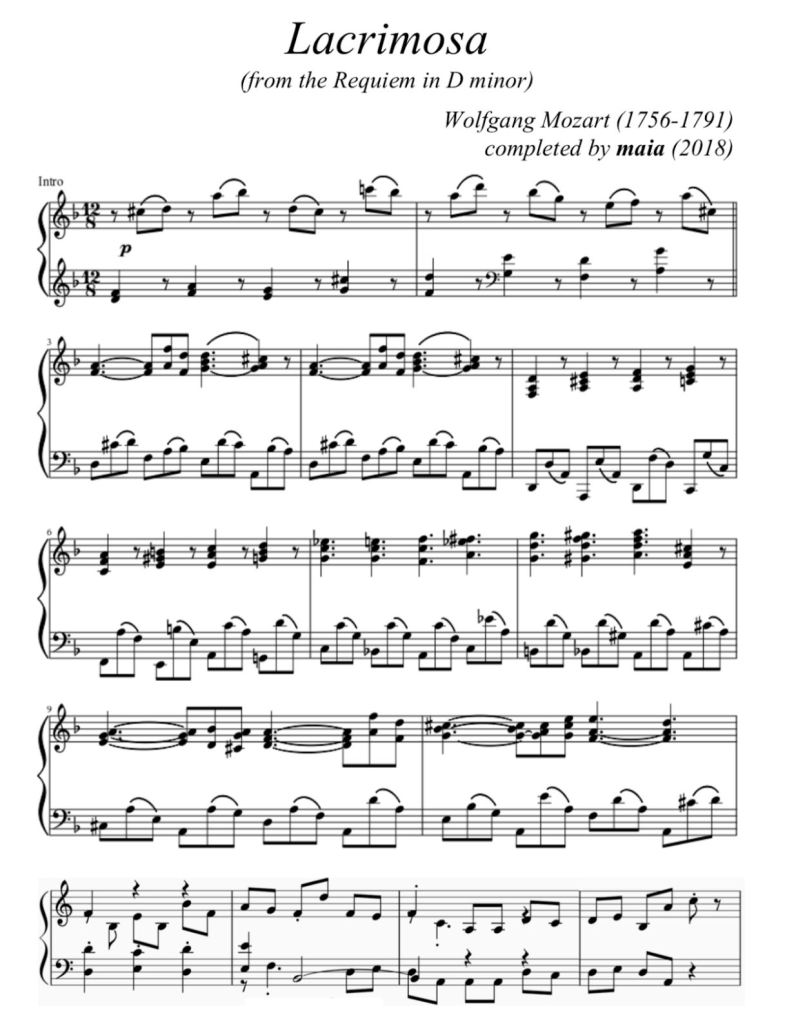

maia is an AI music generator trained on Mozart’s pieces and tasked to finish the Lacrimosa movement in Mozart’s Requiem – which he had famously written till the first eight bars at the time of his passing.

Background

We started out with the intention of creating an AI that could complete Mozart’s unfinished composition Lacrimosa — the eighth sequence of the Requiem — which was written only till the eighth bar at the time of his passing.

We ended up creating a deep neural network called maia — play on the term ‘music ai’ — that can generate original piano solo compositions by learning patterns of harmony, rhythm, and style from a corpus of classical music by composers like Mozart, Chopin, and Bach.

We approached this problem by framing music generation as a language modeling problem. The idea is to encode midi files into a vocabulary of tokens and have the neural network predict the next token in a sequence from thousands of midi-files.

Data

We used a corpus of midi files from https://www.classicalarchives.com — comprising 1500+ piano solo compositions from 24 classical composers like Mozart, Chopin, and Bach. These midi files were then encoded into 2GB of text files containing sequences of varying lengths of tokens from 300 to 80,000.

Metrics

Generative models are categorically difficult to evaluate objectively. We may use the quantified metric of BLEU score as proposed and demonstrated by Yu et al. in the SeqGan paper [1], to see the similarity of the generated sequences as compared to sequences from the training data.

An alternative way of evaluating the model is to see how well the generated music is able to be distinguished from real ones. Qualitatively, we used human subjects to try and distinguish which music sequence is composed of the human and which are generated by the neural net.

Implications

Prior works in sequence generation of sequences have largely been concentrated in natural language. Here we seek to explore if the effectiveness of sequence models can be extended to other types of similarly structured data. Additionally, we want to explore if we can architect a model to generate sequences of discrete tokens that not only mimics short term patterns but also model longer term dependencies.

In music generation, rhythm and melody will be the short term patterns while form and structure will constitute the longer term patterns.

Approach

Encoding

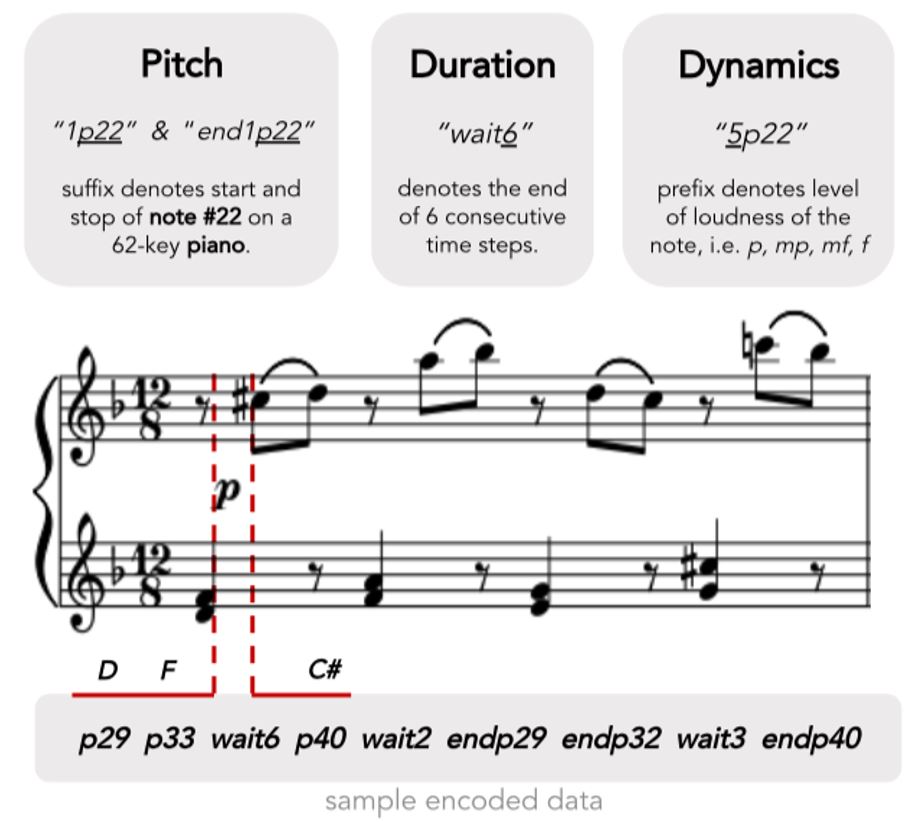

We used MIT’s music21 library (http://web.mit.edu/music21/) — a toolkit for computer-aided musicology — to deconstruct the midi files into their fundamental elements: duration, pitch, and dynamics.

Next, we adopted the ‘Notewise’ method [2] proposed by Christine Payne’s — a technical staff at OpenAI’ — to encode each composition’s duration, pitch, and dynamics into a text sequence — resulting in a vocabulary size of 150 words. Each midi file is sampled 12 times per quarter note to encode triplets and 16th notes.

Additionally, to augment our dataset, we used modulations to duplicate every piece by twelve times — each, one note lower than the next.

Tokenizing and sequencing

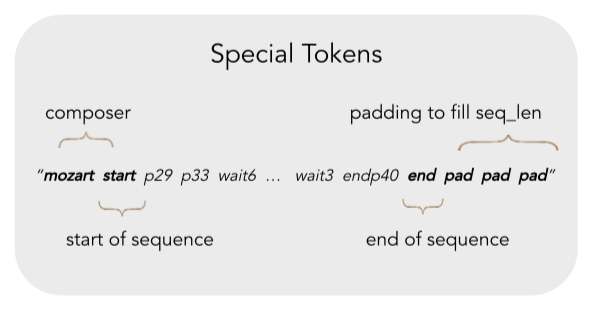

We explored added special tokens to each piece so that the sequence would contain information about the composer, when the music starts and when it ends. This will be important for the GPT model that we use later.

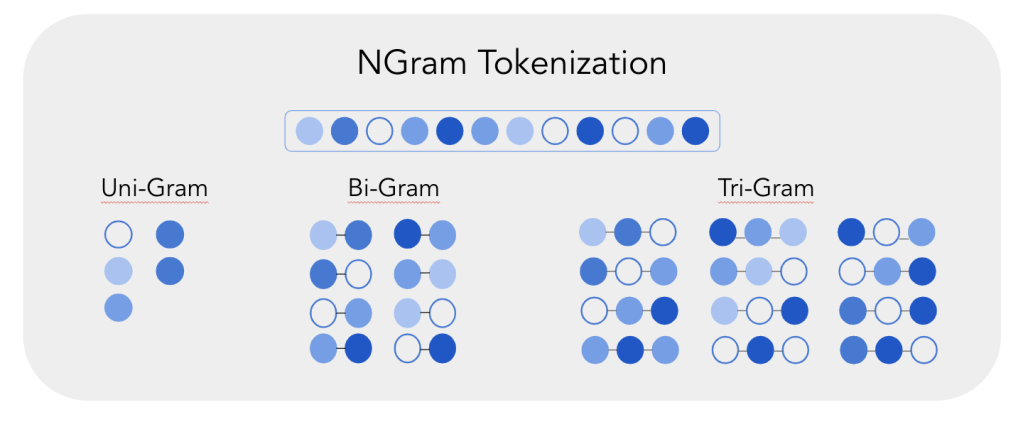

We also explored NGram Tokenization, which treats a string of n consecutive ‘words’ as a single token. The motivation was to see if we can better capture the semantics of compound ‘words’ that represent common chords or melody patterns. Eventually, we still stuck with unigram tokens for our final model, as any higher order of ngram increases the vocabulary size substantially compared to our dataset.

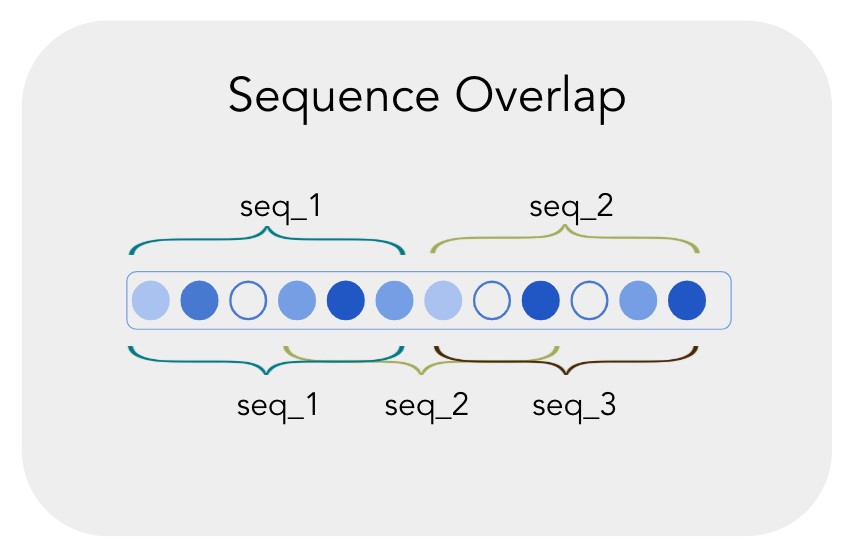

Next, the encoded text data were batched into sequences of 512 tokens for training. Instead of just chopping them up into mutually exclusive sequences, we overlapped the sequences i.e. every subsequent sequence share 50% overlap with the previous sequence. This way, we wouldn’t lose any information of continuity at the points which split the sequences.

From this method of batching, we yielded 500k examples of sequences that contain 512 tokens.

Two layers stacked LSTM

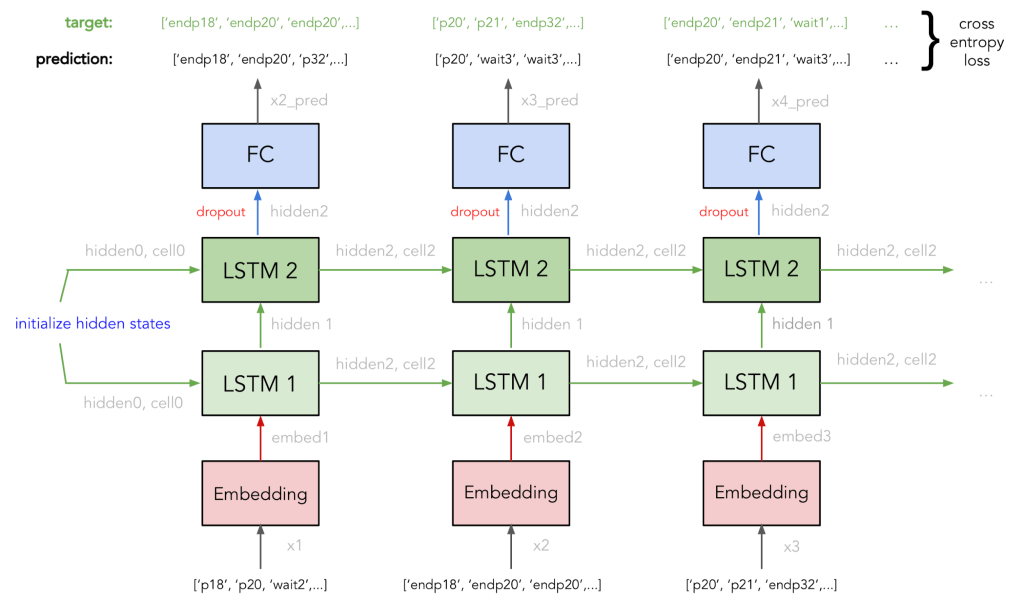

The first version of maia was built using a recurrent neural net architecture. In particular, we used LSTM because its additional forget gate and cell state was able to carry information about longer-term structures in music compared to RNN and GRUs — allowing us to predict longer sequences of up to 1 minute that still sounded coherent. Our baseline model is a 2-layers stacked LSTM with 512 hidden units in each LSTM cell. Instead of one-hot encoding the input, we used an embedding layer to transform each token into a vector — the embedding dimension we used is 150^(0.25) ≈ 4. The loss function for our LSTM model is cross-entropy.

To ensure that our generated sequences are diverse, instead of always selected the most likely next token in the prediction, the model would randomly sample from the top k most likely next tokens based on their corresponding probability, where k is between 1 and 5.

There were hyperparameters that we had to tune, such as deciding the sequence length per sample. Too short and you will not learn enough to produce a string of music that sounds coherent to human. Too long a sequence and training will take too long without learning more information.

Optimizing our batch size will also allow us to trade off learning iterations vs leveraging on GPU’s concurrent computation. We used a grid search to find the best combination of sequence length and batch size.

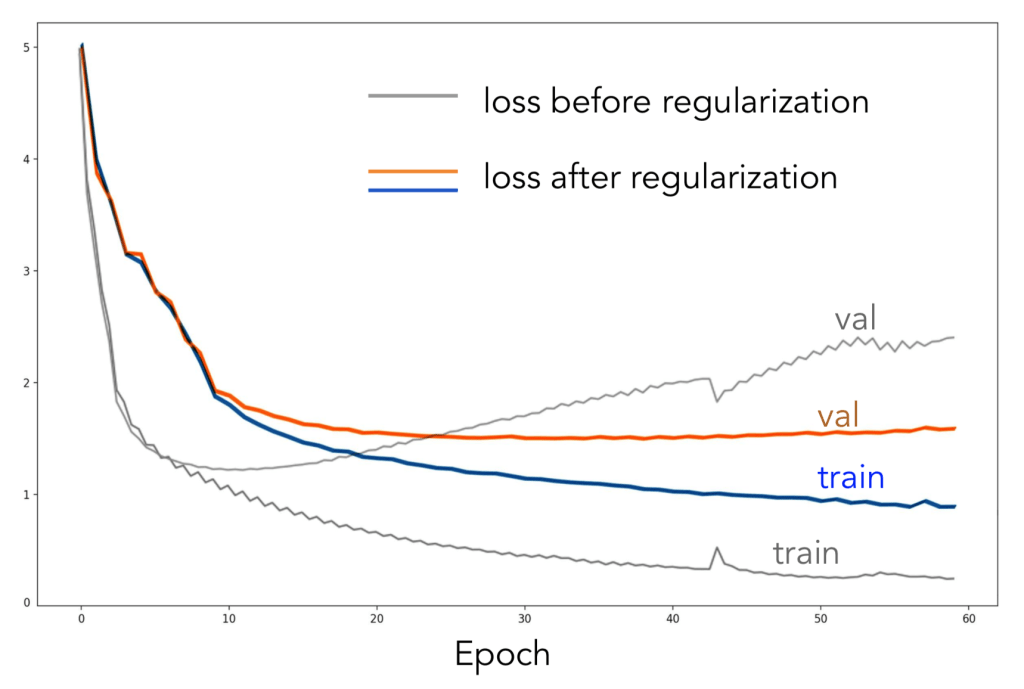

We also set the weight decay attribute in the Torch LSTM module to non-zero so that our model penalizes large weights and ultimately reduces overfitting. This is the equivalent of L2 regularization for LSTM.

We observed that the ability of the LSTM model in generating coherent sequences started to fail after 512 tokens. Additionally, for sequences longer than 512 tokens that were generated by the LSTM model, there was not any discernible pattern of musical form or structure. Our empirical results seem to agree with theoretical postulations that even with LSTM, recurrent neural nets face difficulties learning dependencies of longer paths.

For this reason, we decide to use the Transformer model which leverages self-attentional networks to better model long term dependencies [3].

Transformer – GPT

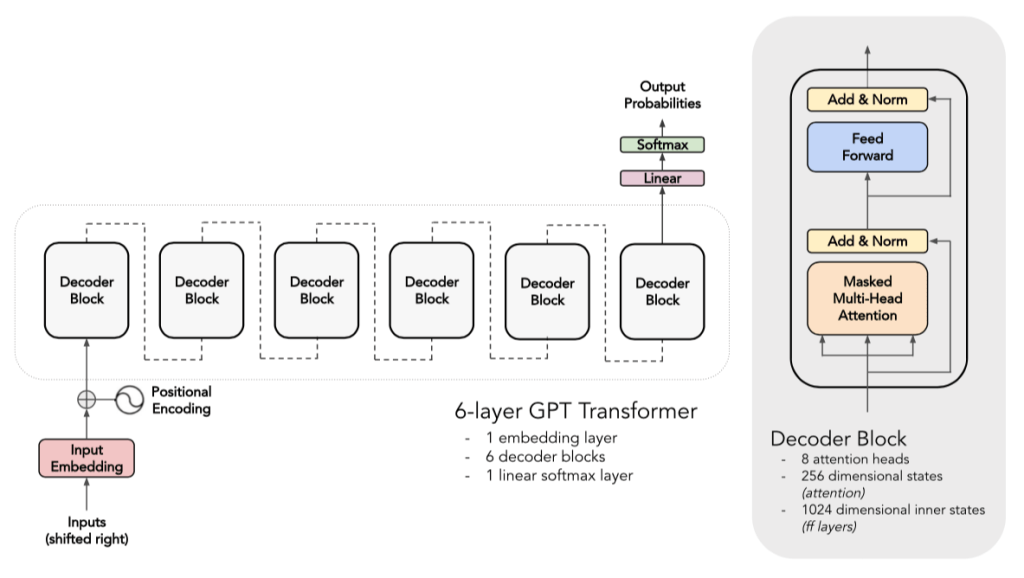

Specifically, we used the Generative Pre-Training (GPT) variant of the Transformer model that was proposed by OpenAI [4]. The effectiveness of GPT was first demonstrated in generative language modeling through training on a diverse corpus of unlabeled text data. The GPT model is essential the vanilla Transformer model with its encoder block and cross-attention mechanism stripped away — so that it can perform more efficiently on unsupervised tasks.

We used a 6-layers GPT model that included one embedding layer, 6 decoder blocks and 1 linear softmax layer that will return us the logits for the next predicted token. Each decoder block has 8 self-attention heads with 256-dimensional states and 1024 dimensional inner states for the feed-forward layers.

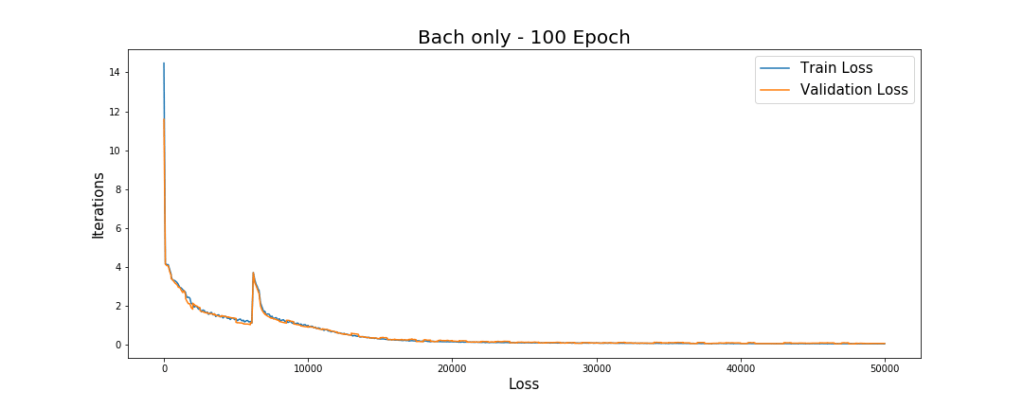

Of the 500k sequences that we obtained from preparing the data, 95% was set aside as training data while 5% was used for validation. None of the datasets we had were allocated as the test set since we are working with a generative model.

Using data from all composers, the training loss converged after about 5000 iterations. However, we decided to push the training to 200k iterations (30 epoch) — which took approximately 60 hours — to see if we could get higher quality generated samples.

Our initial results were not particularly coherent so we tightened the training to a single composer.

Overall, our attempt to model longer sequences were hampered by the memory of the GPU we were using. It can only support up to 512 tokens in each sequence.

GPT-2

We also tried to implement our model on the latest state-of-the-art GPT2 from OpenAI [5] who released part of the code and a smaller model with “only” 117 million parameters. This model is very similar to the previous GPT. In a nutshell, GPT2 was trained with more parameters and on a bigger and more diverse dataset that was scrapped from the internet.

We had to make a choice between using the pre-trained model or build it from scratch. The first solution would allow us to take advantage of the large dataset the model was trained on, but because it was trained on text and not music, it may not generalize well with our dataset. The second solution would make more sense as the model would only learn from music data, but the size of the dataset would reduce the amount of total training and thus the overall performance.

We decided to go for the first solution, as our encoding was still very close to a natural language, we thought that transfer learning would make more sense.

However, the binary encoding part of the GPT2 does not fit our tokenizing and sequencing. As we thought that our data encoding was a crucial part of our method, we did not want to process it again. That is why we decided that using this novel model was not worth breaking apart our data.

Yet, last Tuesday, OpenAI released another model with 345 million parameters and shared the biggest models with AI & security communities. Using the new one might be a good incentive to push us to change the way our data is encoded as the benefit of building on top of such a big model may outperform our current model.

Sparse Transformers

Because of the limitations of our GPU that restricts us to 512 tokens, we decided to experiment with the new Sparse Transformer from OpenAI. The goal of this model is to build upon the transformer by changing the self-attention mask.

Indeed, in the vanilla transformer, each token attends to every other token, which creates a quadratic complexity over the sequence length O(n²). Thus, by changing the computation of the attention, we can reduce the complexity to O(sqrt(n)*n) which would, in our example would reduce the computations by a factor of 20.

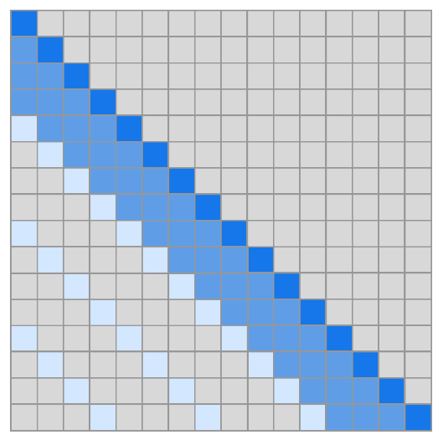

The first method is called strided attention. Just like in a convolution layer, the goal is to use the stride to jump a certain number of cells to attend every X cell as shown in the matrix below:

However, this method does not work well if we deal with data that has period patterns, which is what music basically is. Thus, it makes more sense to use the other method: fixed attention.

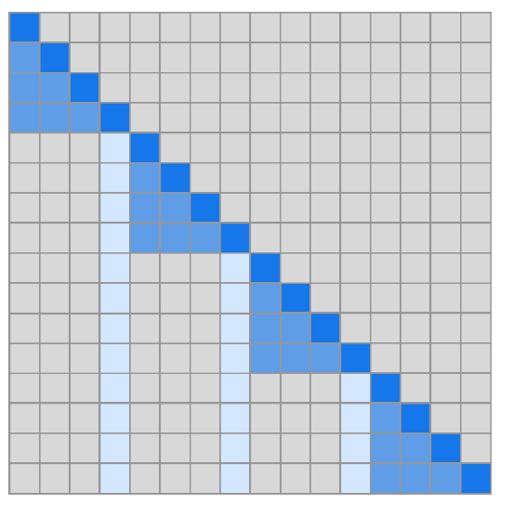

Fixed attention has the same mechanism, meaning that we want to attend so only a subset of the sequence. However, in that case, we want a group of X tokens to attend to the same column. Thus, the periodicity is broken down and the model can attend to a great variety of tokens that are not necessarily all spaced the same way.

Additionally, we thought that another sparse attention mechanism specific to music would be interesting. We will investigate further to find how relevant that would be. We should get in touch with Carmine Cella, Assistant Professor at Berkeley in the music department as he worked on music representation and applied mathematics. He must be a great expert that would help us build a more tailored sparse transformer.

Finally, in order to speed up the computations of these attention mechanisms, OpenAI built GPU kernels that are specifically built to handle these matrices. The average speedup is around an order of magnitude faster than what was previously used.

Results

BLEU score

A quantitative metric that can be recursively, quickly and accurately applied to our models is the BLEU score. BLEU evaluates the number of ngrams used in the generated sequences that were also present in some reference sequences. It is widely used to evaluate translation models. It assumes that good sequences look similar to real sequences at a micro level. This is a reasonable assumption as we expect our generated pieces to contain similar patterns of harmony, rhythms, and style.

Yet, our problem here is quite different from a translation one. We are not comparing one given translation with only a limited number of way to express it. We are generating completely new sequences of music based on a couple of notes, involving other components as creativity and consistency.

This has several consequences. First, small ngrams are less informative. Indeed as we are using a large set of compositions in our reference document, we expect the 1-gram value to be one (we are not going to use a new note in our composition) and 2-grams and 3-grams quite close to one too, as most of those combinations have been used in some existing compositions. As a result, the information of those ngrams is lower. In addition, we would love our generated compositions to have some sort of originality. We do not want to recreate or regurgitate existing sequences in the training data but really creating something new and unique that was inspired by existing music — just as an artist would do. Consequently high n-grams should also be less valued and very high n-grams not even considered.

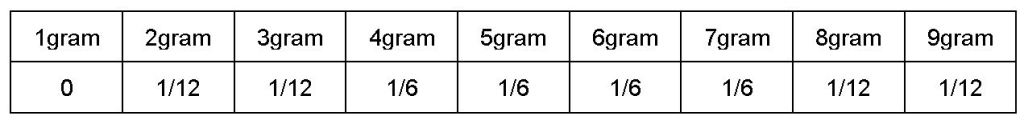

Based on all of those considerations, we constructed a customized BLEU score. The chosen weights are:

We used the BLEU score to compare our LSTM baseline model with some real compositions of Mozart. The results — averaged on a dozen of sequences — are 0.25 for the LSTM and 0.14 for the real data. This means that our generated samples are good on our customized metrics. The higher score that LSTM compositions yield over real compositions underline the presence of overfitting where the generate music contains substantial repetitions from the original data.

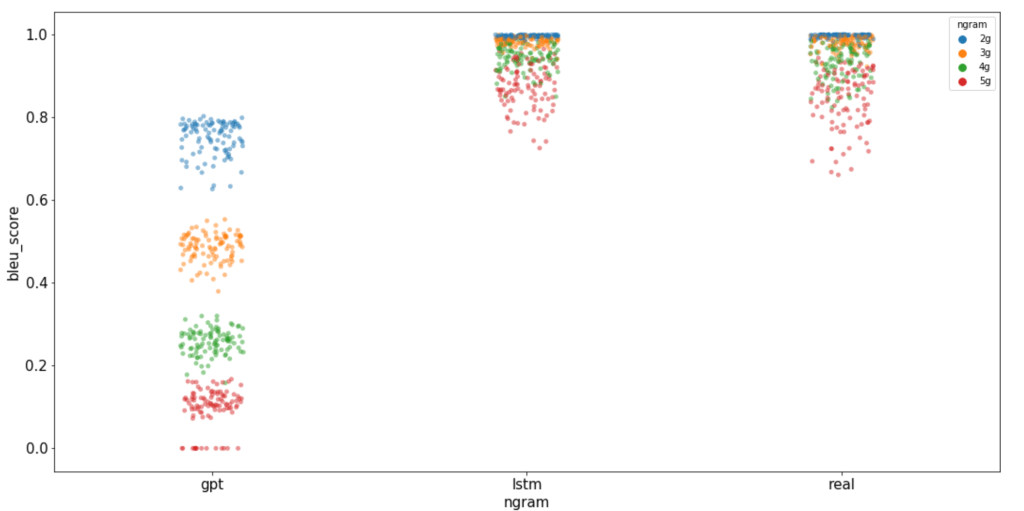

For GPT, we faced a different challenge. Our version of the GPT struggled to learn long term patterns and, as a result, scores very low on high ngrams (6 and more). This highlight that our new compositions are probably more originals but also less faithful to the music rules and therefore show less structure and less general harmony.

Consequently, to compare our GPT with the baseline model and real data, we visualized the cumulated ngrams (from two to five). Using a strip plot, we can directly visualize the information that our model retain, and those that he does not. Overall, the GPT scored lower for every cumulated ngrams, strengthening the patterns previously observed.

This result is surprising. We expected the GPT to score higher than the LSTM. Some explanations could be: our GPT need to be optimized for our tasks, the models need more data to perform well. Also the architecture or the parameters need to be changed. To address this problem of underfitting, we started to explore more sophisticated embedding, further tuning, gathering more data as well as the use of sparse transformers.

Samples of generated musics

LSTM samples

GPT samples

Demo

We also built a demo that allows people to input their custom prompt (any music sequence they would like the composition to start with) then have maia finish the rest of the piece for them. This was demonstrated during the 282 Poster Presentation and will be uploaded to Github shortly.

Tools

GCP AISE: 2vCPU, 1 Nvidia Tesla P100, 7.5G RAM, 100GB Disk Size, PyTorch

GCP AISE: 2vCPU, 1 Nvidia Tesla P100, 7.5G RAM, 100GB Disk Size, Tensorflow

MIT music21: Toolkit for Computer-aided Musicology

MuseScore 465722e

References

[1] L. Yu, W. Zhang, J. Wang, and Y. Yu. Seqgan: Sequence generative adversarial nets with policy gradient. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.05473, 2016.

[2] C. Payne. Clara: A neural net music generator. http://christinemcleavey.com/clara-a-neural-net-music-generator/. 2018.

[3] A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, Ł. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 6000–6010, 2017.

[4] Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. URL https://s3-us-west-2. amazonaws. com/openaiassets/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language understanding paper. pdf, 2018.

[5] Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., & Sutskever, I. (2019). Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. https://d4mucfpksywv.cloudfront.net/better-languagemodels/language-models.pdf.

[6] C. Payne. MuseNet. thttps://openai.com/blog/musenet/. 2019.

[7] S. Gray, A. Radford, and D. P. Kingma, GPU Kernels for Block-Sparse Weights. https://blog.openai.com/ block-sparse-gpu-kernels/. 2017. f

Team contribution

Edward (40%)

- midi files gathering

- midi-to-text encoding

- music21 exploration

- setting up and managing GCP dev environments

- buidling the baseline lstm model

- review transformer and GPT papers

- illustrating transformer and GPT model

- building vanilla GPT model

- training and tuning the vanilla GPT

- writing a custom prompt music generation demo

- generating samples and going through them

- poster: neural rhapsody, encoding, data & tokens, lstm, transformer (gpt)

- Report

Andy (30%)

- Review of state of the art approaches for music generation (papers review)

- Review of state of the art approaches for evaluation of music generation (overview of the metrics used to evaluate results)

- Music21 exploration and tests

- Generation of compositions with the GPT model

- Construction of a customized BLEU score to compare different approaches

- Visualization of cummulated ngrams

- Comparison of the quality of the compositions from the different models

- Report

Louis (30%)

- Review of state of the art approaches for music generation

- Review of state of the art approaches for data encoding

- Analysis of music theory and counterpoint implementations in computer generated music and deep learning models

- Music21 exploration and tests

- GPT2 implementation

- Sparse Transformer implementation

- Poster: Sparse Transformer

- Report